Ecology of Rockweed

References and resources: The 2014 Maine DMR Fishery Management Plan, which has not been implemented, has an excellent review of the ecology of rockweed. Opportunities for citizen scientists to get involved in studying rockweed include Project ASCO (Schoodic Institute) and Signs of the Seasons (University of Maine).

Is rockweed a plant?

Rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum) is a type of brown alga. The term “rockweed” suggests that these organisms are plants, but botanically speaking they are not classified as plants because they do not have an internal vascular system. Most plants also have roots, allowing them to obtain water and nutrients from soil. Instead, rockweed has a strong “holdfast” that cements it onto rocks, and rockweed fronds absorb nutrients directly from seawater. Like most vascular plants, rockweed grows by photosynthesis using energy from the sun.

Algae are often referred to as plants informally, for example by commercial seaweed companies such as Maine Coast Sea Vegetables (https://seaveg.com/) and Acadian Seaplants (https://www.acadianseaplants.com/). The 2014 Maine DMR Fishery Management Plan also refers to rockweed as a plant.

Distribution and establishment

Rockweed is the most abundant intertidal seaweed along Maine’s rocky coast, extending into the Canadian Maritimes and much of the North Atlantic. This slow-growing, perennial alga is most common in sheltered coves, estuaries, and bays where it is protected from strong wave action and ice shear. Rockweed can reach heights of ~3-6 feet when relatively undisturbed.

Rockweed is the most abundant intertidal seaweed along Maine’s rocky coast, extending into the Canadian Maritimes and much of the North Atlantic. This slow-growing, perennial alga is most common in sheltered coves, estuaries, and bays where it is protected from strong wave action and ice shear. Rockweed can reach heights of ~3-6 feet when relatively undisturbed.

photo: Maine Sea Grant

Rockweed co-occurs with Fucus vesiculosis (bladderwrack) and other Fucus species, which are better at tolerating exposed, open coasts without being torn off by waves and ice. Fucus vesiculosis is easily distinguished from rockweed by its flatter fronds with a prominent midrib and paired air bladders. Both species occur in intertidal areas, but rockweed can form a thick monoculture in the mid- and lower intertidal zone by shading and outcompeting other algae. When storms and other disturbances scour rockweed from the substrate, it is often replaced by Fucus vesiculosis, which has a longer reproductive season and recruits more quickly than rockweed.

In spring, female and male rockweed plants shed eggs and sperm into the water where they mingle and fuse to form embryos. Simultaneously, a beneficial fungus that lives within the rockweed releases spores that infect the young rockweed embryos as they drift and settle onto a suitable rocky substrate. This obligate symbiotic fungus, Mycophysias ascophylli, is thought to aid in the desiccation tolerance of rockweed. Fungal filaments grow throughout the tissue of the rockweed plant with no obvious visible sign of their presence until both the seaweed and the fungus form new reproductive structures in spring, repeating the cycle of releasing gametes and spores.

Young rockweed plants grow slowly and eventually produce a strong basal holdfast that is cemented onto the rocky substrate. However, juveniles often perish due to grazing by the invasive common periwinkle (Littorina littorea). Individuals that survive may live for decades as long as their holdfast remains intact. Lateral branches form along the main shoot and grow taller with sufficient light, while the holdfast thickens over time. Adult plants actually benefit from grazing by periwinkles because the periwinkles remove epiphytic algae that start to grow on surface of rockweed fronds. In addition, rockweed constantly sheds its outermost cells to prevent epiphytes from smothering it. Older plants produce phenolic compounds as a chemical defense against grazers. These characteristics make rockweed an extraordinarily hardy and long-lived seaweed of rocky coastlines.

Rockweed as a habitat

Rockweed is the most important foundational species of the intertidal zone in Maine, providing an essential habitat and feeding ground for more than 150 species (Seeley and Schlesinger 2012; DMR 2014). In this sense, rockweed beds are similar to Maine’s salt marshes. Other ecosystem services include buffering wave action at high tide, contributing to detrital food webs, and protecting marine invertebrates from desiccation at low tide. During low tide, invasive green crabs are common under rockweed, while threatened blue mussels find refuge in rock crevices covered by rockweed.

(photo: R. H. Seeley)

Periwinkles, amphipods, isopods, and many other invertebrates serve as prey for larger species that visit rockweed beds. Fish that forage in this habitat include American eel, threespine stickleback, pollock, rock gunnel, alewives, and Atlantic mackerel. The lower rockweed zone also supports cod, tomcod, northern pipefish, tautog, winter flounder, and occasionally lobster (during nocturnal high tides). In spring, rockweed plants release copious amounts of energy-rich gametes that are consumed by zooplankton.

At the water’s surface, floating mats of rockweed are a preferred feeding habitat for eider ducklings before they are able to dive deeper to feed. During low tide, shorebirds such as lesser yellowlegs, ruddy turnstones, gulls, and many other species feed on invertebrates living in rockweed and along windrows of detached fronds that have washed ashore.

Effects of harvesting

Commercial-scale extraction of rockweed from the rocky intertidal zone can degrade and diminish this habitat for other species and deprive coastal food webs of organic matter. About 15-20 million pounds of rockweed are harvested in Maine each year, an amount that seems likely to increase due to commercial interests and the high value of processed rockweed.

Discussions about the effects of harvesting are complicated because the intensity, frequency, location, and scale of harvesting vary tremendously along the coast. It is misleading to refer to any “effects of harvesting” without this context. Also, testing for effects of different harvesting practices on rockweed and the highly mobile species that use this habitat is extremely challenging. In some cases, studies are inconclusive due to insufficient data and/or intractable research questions. Most scientific studies of effects of harvesting are small-scale and of short duration, typically involving a single “harvest event” followed by only 1-2 years of monitoring.

A recent study by Johnston et al. (2023) has received a lot of publicity, some of which is misleading (see op-ed piece by David Porter). A publication by Seeley et al. (2024) identified statistical errors and other reasons to question the main conclusions of this study, which was followed by a response by Johnston et al. (2024).

Several studies have shown that rockweed biomass can grow back from a single harvest event within a few years, but the plants are shorter and bushier than the intact rockweed forest that preceded them (DMR 2014). In the absence of harvesting, most of the plants’ biomass is concentrated in the canopy, where growing fronds branch and proliferate. This upper portion of the plant is cut off and removed by harvesters using rakes or mechanical harvesting boats. Large amounts of rockweed also break off naturally, especially during storms.

Much has been written about whether commercial-scale rockweed harvesting is “sustainable.” From a commercial standpoint, harvesting on a ~3-5 year cycle may be profitable in some areas, but this begs the question of how rockweed extraction has affected the local ecology. Removing biomass and the tall canopy of wild rockweed habitats is bound to affect birds, fish, crustaceans, mollusks, small invertebrates, and other species that depend on this habitat, especially species that forage and find shelter amongst floating rockweed fronds. For a detailed discussion of ecological (vs. commercial) sustainability, see Seeley and Schlesinger (2012) and Lotze et al. (2019).

Rockweed Management in Maine

What is the 2014 DMR Management Plan?Cobscook Bay, near the border with Canada, has its own management plan that designates conserved no-harvest areas and stipulates where rockweed can be harvested based on biomass assessments. No such plan exists for the remaining coastline of Maine.

In 2014, the DMR published a Fishery Management Plan for Rockweed, but this planning document has not been implemented. Nonetheless, a great deal of effort went into developing the 2014 report and a few highlights are summarized here.

In 2014, the DMR published a Fishery Management Plan for Rockweed, but this planning document has not been implemented. Nonetheless, a great deal of effort went into developing the 2014 report and a few highlights are summarized here.

Members of the Rockweed Fisheries Plan Development Team (PDT) included Jane Arbuckle (Maine Coast Heritage Trust), Dr. Brian Beal (University of Maine at Machias), Dr. Susan Brawley (University of Maine), Susan Domizi (Source Maine), Dr. Linda Mercer (ME DMR), Dave Preston (North American Kelp), George Seaver (Ocean Organics), Nancy Sferra (The Nature Conservancy), Pete Thayer (ME DMR), Dr. Raul Ugarte (Acadian Seaplants), and Chris Vonderweidt (ME DMR, Chair).

The PDT reviewed basic and applied research on rockweed harvesting and came up with a series of recommendations. Most of their recommendations were related to commercial interests, but several aspects of the Management Plan addressed concerns about unwanted ecological effects of intensive harvesting.

For example, Recommendation 3 (no-harvest areas):

“The PDT recommends that the Department implement no-harvest areas that consider the impact of rockweed harvest, if any, on sensitive wildlife areas (e.g., shorebird habitat, seal haul out, previously mapped critical areas) and conserved lands.”

“Additionally, the PDT recommends that the Department implement reference sites along the coast and control plots in and/or around sectors. Establishing these no-harvest research areas will allow for comparisons between harvested and natural areas to evaluate the long-term impacts of harvesting on rockweed beds.”

The PDT also identified many questions in need of research, a few of which are listed below. These are challenging questions that will require a great deal of time and effort.

The PDT called for research on:

“Biomass Assessment

Evaluation of long term effects of harvesting techniques as permitted by the Department and in use in Maine on defined areas at commercial scale; especially, how canopy structure (height) is affected.

Periodic re-evaluation of natural mortality vs. harvest mortality, especially if hurricane incidence increases or other effects of warming water and invasives are deemed potentially serious.

Ecology and Habitat

How does structural change from harvest benefit/detract from habitat?

How does architecture of rockweed affect associated species?How much loss/change is too much?

Effects of Harvesting

Assess the long-term effects of harvesting on a large spatial scale.

Will cumulative effects of successive harvest restructure habitat and/or ecosystems?”

**********************************************************************************************

In the absence of additional DMR oversight, a worst-case scenario could be that harvesting pressures increase along parts of the Maine coast without any restrictions to protect affected rockweed beds from over-exploitation and long-lasting ecological damage.

As long as the Maine 2019 Supreme Court decision remains in place, upland property owners have the right to deny permission for rockweed harvesting on their land. However, this contingency does not constitute a management plan that addresses both conservation issues and the interests of commercial harvesters.

A recent publication in the Maine Policy Review by Hannah Webber and colleagues discusses next steps that could be considered for implementing a rockweed management plan for Maine. The abstract of their article states: “Sustainable harvest of seaweed species is both economically and ecologically important in Maine. Management of these resources in Maine targets the intertidal foundational species, rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum). Delayed adoption of the rockweed fisheries management plan, drafted in 2014, presents an opportunity to re-examine the plan from an ecosystem-based management perspective. Our comparison of such studies to the drafted plan reveals that many of the critical elements are included. With additional management strategies, Maine could set a standard of ecosystem-based management for a foundation species and can position itself as a global leader in management of wild, and farmed, seaweed harvesting.”

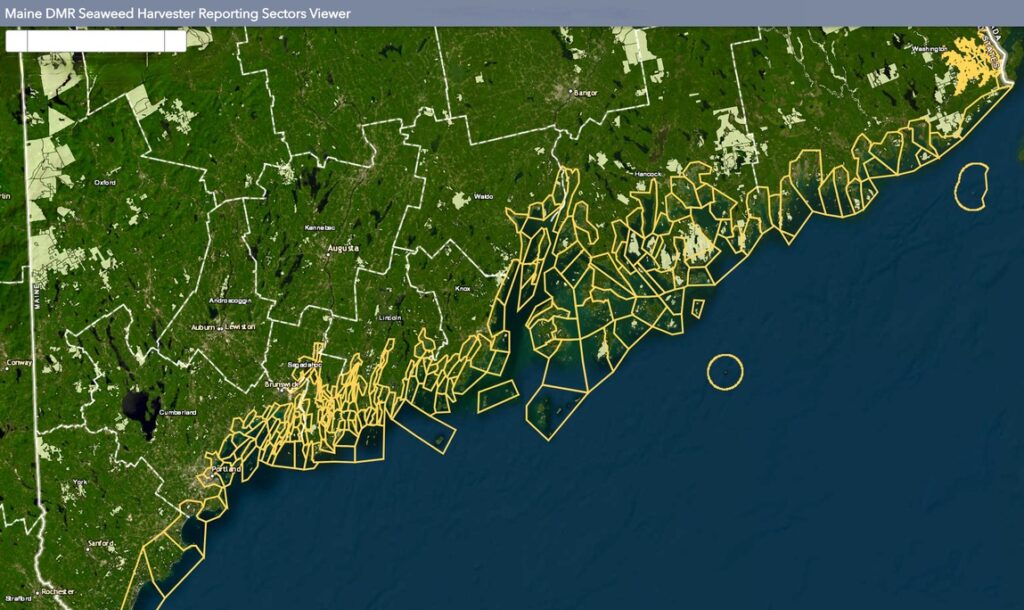

The entire Maine coastline is divided into sectors for commercial rockweed harvesting.